In the absence of meaningful climate change policies, investors[1] are seeking insights into companies’ climate risks through the development of detailed climate-related financial disclosures[2]. We see this increasingly too across regulatory bodies and supported by financial institutions[3]. In 2018 the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) released a paper which surveyed ASX-listed companies’ latest public disclosures to identify whether they specifically identified climate risk as a material risk in their operating and financial reviews. ASIC stated that it expects listed companies to provide meaningful and useful risk disclosure to enable investors to make fully informed decisions.

There is also growing consensus in legal theory that because climate change is a material financial risk, consideration and planning for climate change is consistent with existing common law and directorial duties in Australian law. As such, a failure to consider climate change risks, and/or inadequately or deficiently consider climate change risk exposures, may be in breach of directors’ duties of due care and diligence[4].

In this article we examine the how climate change is altering the physical environment, how businesses are responding and the expectations of the market.

What is the message from climate scientists to business[5]?

In February this year, Dr Helen Cleugh, Climate Science Centre Director at the CSIRO wrote in the Financial Review calling the attention of business to the science behind Australia’s “hottest, wettest, dustiest, and generally most extreme (summer) on record”. What she asked readers to consider is perhaps best captured in the following statement:

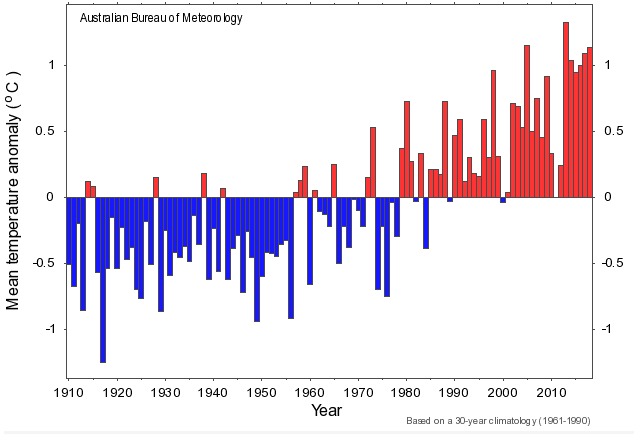

“The temperature increase Australia has experienced is within the range of our earliest climate change projections, which CSIRO published almost 30 years ago. In other words, our climate models adequately capture the processes that cause the long-term warming trend, which in turn means that our projections of future climate change are realistic, plausible and importantly, can allow us to plan.”

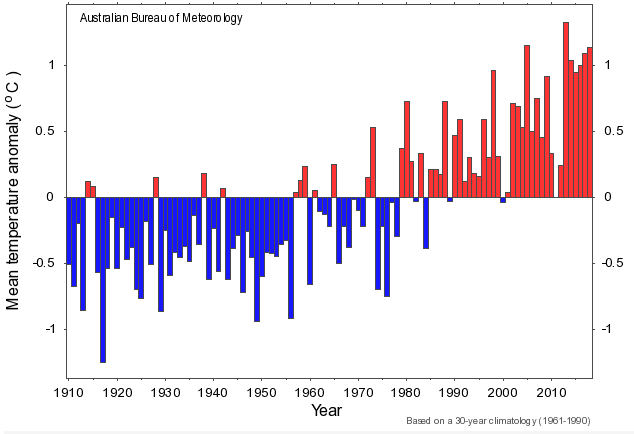

Certainly, as seen in Figure 1, compared to 1910, Australia has already observed an increase of 1oC.

Figure 1: Australia’s observed climate change since 1910, State of the Climate, Bureau of Meteorology.

She also noted that in working with the Bureau of Meteorology, using supercomputers, a “fully coupled climate and Earth system model” has been developed, which “has significantly improved the accuracy of weather forecasts, including for high impact weather such as tropical cyclones, fire weather and heavy rain; along with providing global climate simulations for long-term climate projections. However, the key message from our most recent climate change projections is unchanged: if global greenhouse gas emissions continue on their current (high emissions) trajectory then these warming trends will continue, and the climate impacts we are seeing will continue including more extreme weather events.”

Finally, Dr Cleugh stated, “If this summer has underscored one thing it is that strategies for adapting to climate change must sit alongside those for mitigation. CSIRO research supports both.”

Working with numerous top ASX listed companies Energetics has found that the most comprehensive approach to assessing and managing climate risks used the guidance established by the Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) together with the scientific insights available through CSIRO. This way, business is not only informed about the expectations of the investment community but can understand the impacts on their business models of the need to both reduce their greenhouse emissions and adapt to the changing climate.

In the section to follow we outline a framework for climate risk assessment that is informed by climate science.

The TCFD framework and the application of climate science

The challenge with climate change is not to treat it as a ‘special’ issue but rather as a core business planning consideration. The release in June 2017 of the TCFD guidance reflected the concerns of the investment community worldwide that climate risks required a standard method for companies to both assess and disclose. 785 organisations are now supporters of the TCFD including the world’s largest banks, asset managers and pension funds, responsible for assets of US$118 trillion[6].

The TCFD determined that risks are divided across physical risks, which comprise both existential challenges brought about by sustained change such as persistent above-average temperatures and water shortages, as well as severe weather events. The second grouping is transitional risks which arise from a decarbonising economy. These challenges include policy changes (domestic and international), market movements impacting supply and demand, and technology transitions.

The TCFD’s recommendations include the use of stress testing and scenarios as appropriate techniques for the quantification of the risks.

Scenario-based analysis

“Increasingly, financial regulators are also using climate risk scenarios as the basis for stress tests… we encourage entities to perform their own stress tests that consider such scenarios.” Geoff Summerhayes, APRA

Multiple qualitative scenarios covering transition risks and physical risks should be developed which are:

- plausible and credible

- distinct

- consistently developed

- relevant to risks and opportunities identified

- challenging (explores unanticipated events).

However, there are fundamental differences between scenario analysis for transition risks and the approach required for understanding physical risks.

Developing a response to physical risks requires scientific insights. By engaging with the science, business enters a new paradigm. Climate science and associated services in the form of data and information mapped across regions can inform the assessment of risks: though to date this work has been largely absent.

Scenarios examined need to be consistent between both physical and transition risks, and the temptation to ‘cherry pick’ scenarios that potentially deliver better outcomes, should be avoided.

One scenario needs to reflect a low emissions future which is aligned to the scientific advice that global warming needs to be contained to within a 1.5oC on pre-industrial temperature levels.

Treatment of transitional risks

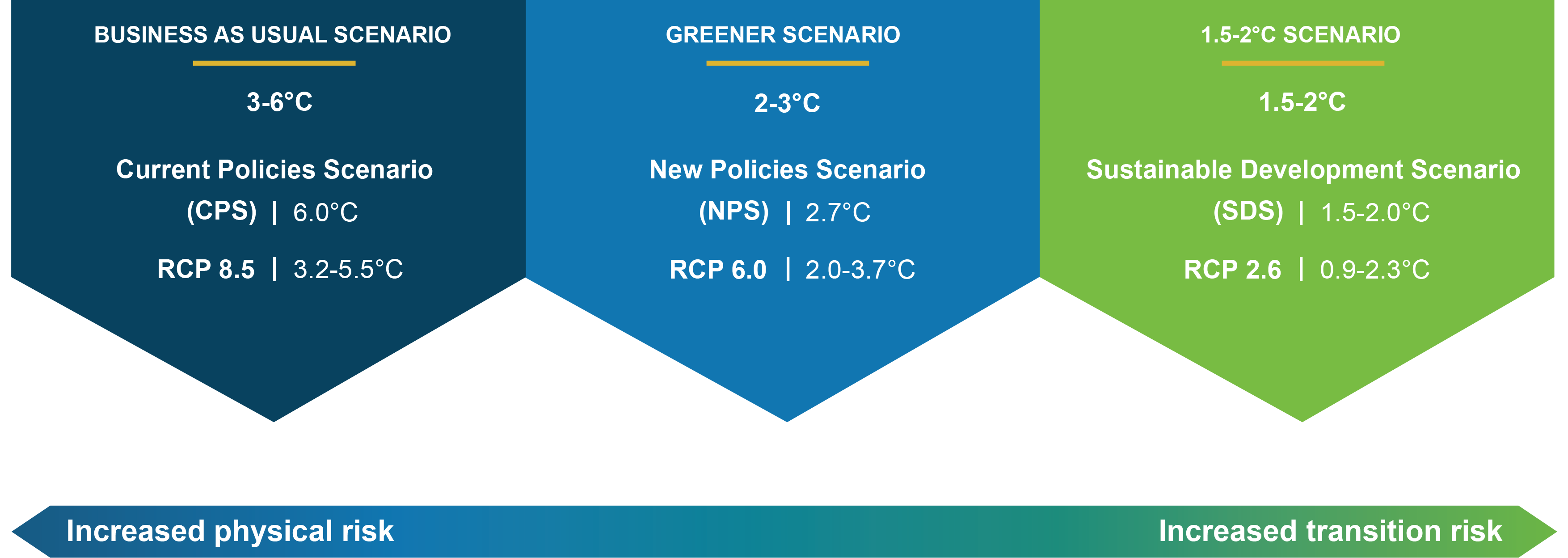

Transitional risks are associated with a decarbonising economy. Assessments typically use scenarios developed by the International Energy Agency (see Figure 2) and Inter-government Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). They incorporate:

- policy changes (domestic and international)

- market movements (supply and demand)

- technology transitions.

Figure 2: IEA World Energy Outlook (2018)

Potential impacts include future scarcity of inputs/products or conversely an oversupply of key inputs/products, new market preferences and the development of new markets, obsolescence, product substitution, the development of incentives and subsidies to support the transition to low emissions technologies.

Treatment of physical risks now and into the future

Physical risk scenarios are not the same as transition risk scenarios. The design and development of forward-looking climate scenarios is a complex undertaking. By its very nature any set of data that defines climate variables (such as daily temperature range and precipitation) in the future is probabilistic: a range of possible future conditions is therefore presented.

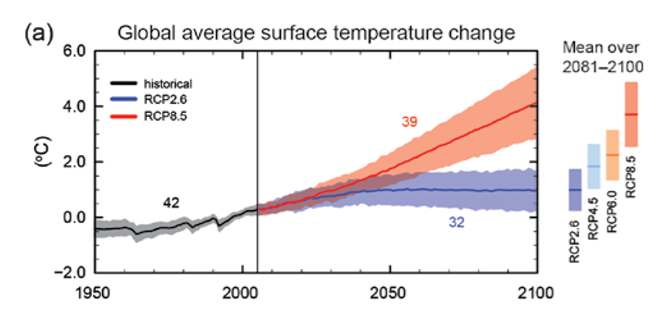

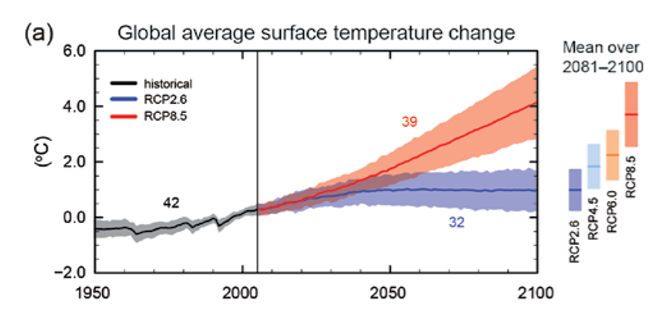

For projections out to 2040 there is effectively only one scenario which aligns with the Paris Agreement. The scenario includes extreme climate events as it is a well-established fact that such events are the main drivers of loss. Under existing climate policies, Australia will experience around 4oC of warming by 2100.

Figure 3: Global warming by 2100: 0.3oC - 1.7oC for low emissions scenario as determined by the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (RCP2.6), and a temperature increase of 2.6 - 4.8oC for high emissions (RCP8.5).

As the features of the individual business and the sector within which it operates require a tailored approach to risk assessment, there are steps that can be followed:

- Use your business’ own organisational data, analyse the portfolio of assets, their locations and therefore their exposure to climate risks

- Determine the most material climate risks for your business, supply chain and customers

- Apply your enterprise-wide risk assessment process which may require developing criteria for assessing climate risk to the business

- Synthesise climate data, indices and approaches with the appropriate company metrics

- Following the mapping, conduct a critical review of outputs. This expert review will identify any anomalies, gaps and weaknesses. Importantly an internal peer review ensures the robustness of the analysis.

Above all, information on climate change risks must meet four criteria. It must be:

- actionable and directly inform enterprise risk management activities

- reportable and aligned with governance and prudential regulatory frameworks

- valuable and build capability within the organisation

- verifiable and therefore peer reviewed to an agreed scientific standard.

Ensuring your business is future ready

While the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) clearly signalled its expectations that the financial sector should “consider climate change in the context of their strategic and operational risk management[7]”, this guidance has implications for businesses in all sectors of the economy. Adopting the recommendations of the G20 Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) enables business to assess the transition and physical impacts of climate change. The elements are:

- Establishing governance over climate risk management and disclosure using the latest legal theory and governance requirements on climate risk in keeping with Australian directors’ duties and ASX guiding principles.

- Alignment with the TCFD guidance using gap analysis, risk assessment and scenario planning. The process can underpin the setting of a science-based target.

- Undertaking a climate risk assessment of the entire business (upstream, operations and downstream) using ISO30001 processes which demonstrate the impact and likelihood of risks in the near to medium term for the senior management team. This assessment provides a clear view of the material risks across operations, supply chains and commodities.

- Complementing risk management frameworks with the best available science and expert assessment

- Developing emissions reductions modelling scoping the task from now through to 2050. From this work, business cases can be developed for:

- investments in energy efficient technologies to reduce energy consumption/demand

- a procurement strategy incorporating on-site generation and a corporate renewable PPA to further reduce costs and exposure to energy market volatility.

- implementation and use of smart energy management systems that can optimise energy consumption and provide valuable business insights.

- Tracking performance and reporting on progress

- Managing climate risk dynamically by monitoring the scientific advice and community concerns.

By combining climate science with business insights, a board can receive robust facts, data and metrics to clearly articulate the management of climate related financial risks, and the ability to project climate driven changes in the value of different assets and their productive capacity.

Michael R. Bloomberg, Chair of the TCFD recently said: “We remain encouraged by the continued growth in the number of companies adhering to the guidelines of the TCFD – it means businesses are better informed about the risks they face, and investors are more capable of making sound decisions. However, we’re also clear-eyed about the serious threat that climate change poses. In order to keep people out of harm’s way, and build a more resilient global economy, we need more companies to follow their lead – and soon[8].”

References

[1] Corporate Governance | Investors support Paris Agreement & TCFD

[2] Goldstein et al | The private sector’s climate change risk and adaptation blind spots

[3] Energetics | Climate risk and the emerging regulatory imperatives

[4] Centre for Policy Development | New legal opinion and business roundtable on climate risks and directors

[5] Australian Financial Review | CSIRO saw this summer 30 years ago

[6] Financial Stability Board | TCFD report finds encouraging progress on climate-related financial disclosure, but also need for further progress to consider financial risks

[7] APRA | The weight of money: A business case for climate risk resilience

[8] Op.cit.