While we are only a couple of weeks into 2021 there are already very clear signposts that 2021 is going to be a year of climate action and climate ambition. While the question remains whether the Australia federal government will stay in the starting blocks where it has comfortably taken up residence, this no longer has much bearing on the corporate imperative to act. Global action is now immutable. Certainly, clear Australian policy would reduce the financial impact of our transition to a low carbon economy; however, the lack of policy is not removing the need for the private sector to deliver real progress on the path to net zero.

So what signposts are we referring to? The three most significant ones to date are the Biden election and the resulting recommitment of the US to the goals of the Paris Agreement, the UK taking over the presidency of COP26 and their obvious drive for ambitious outcomes, and the publication of the Global Risk Report by the World Economic Fund which places global inaction on climate policy as the most significant global economic risk, with infectious diseases relegated to second place. Let’s investigate these in more detail.

Biden recommits the US to the goals of the Paris Agreement

In his first day in office Biden delivered on many of his election promises, signing into effect 15 executive orders which included recommitting the USA to the goals of the Paris Agreement. Once these papers are filed with the UN there is a 30 day wait before they come into effect. This means that before the end of February the US will be throwing its hat into the ring and starting to drive real change. Core to Biden’s campaign were his commitments to a clean energy revolution and environmental justice. He also understands that environment and economy are closely linked. Further, he has committed to “Rally the rest of the world to meet the threat of climate change.”[1] This message has been enhanced by John Kerry, to whom Biden has given charge of climate and national security issues. Kerry has been as fast out of the starting blocks as Biden, addressing multiple American and international meetings in the last two weeks, with a message focused on the need for rapid, concerted, global action by 2030.

UK takes on the complete role of the COP26 presidency

While the UK and Chile shared the role of the COP26 presidency in 2020, mainly as an artifact of the COP being postponed to this year, this year the UK holds the presidency outright. The presidency of the COP might be a ceremonial or figurehead role, however we have seen in the past what a motivated presidency can do when backed by a government with serious climate ambition as was the case with the French COP which resulted in the Paris Agreement.

On 8 January 2021, Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP took on the full time role as the COP President. An accountant by training with experience in consulting and the finance sector, Alok Sharma has previously been the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Secretary of State for International Development. His parliamentary career has included roles in Treasury, Science and Technology, and Infrastructure. He definitely has the credentials to engage with the breadth and complexity of the challenges that face the world in delivering net zero by 2050.

Mr Sharma has spoken at a number of events already[2], outlining the clear ambition of the UK to drive real outcomes in Glasgow in November this year. His message is direct, “a key goal of my COP26 presidency is enhancing international collaboration”[3]. Noting that as the UK also holds the presidency of the G7 for 2021, they will be well-placed to address these global ambitions.

Global Risk Report of the World Economic Forum

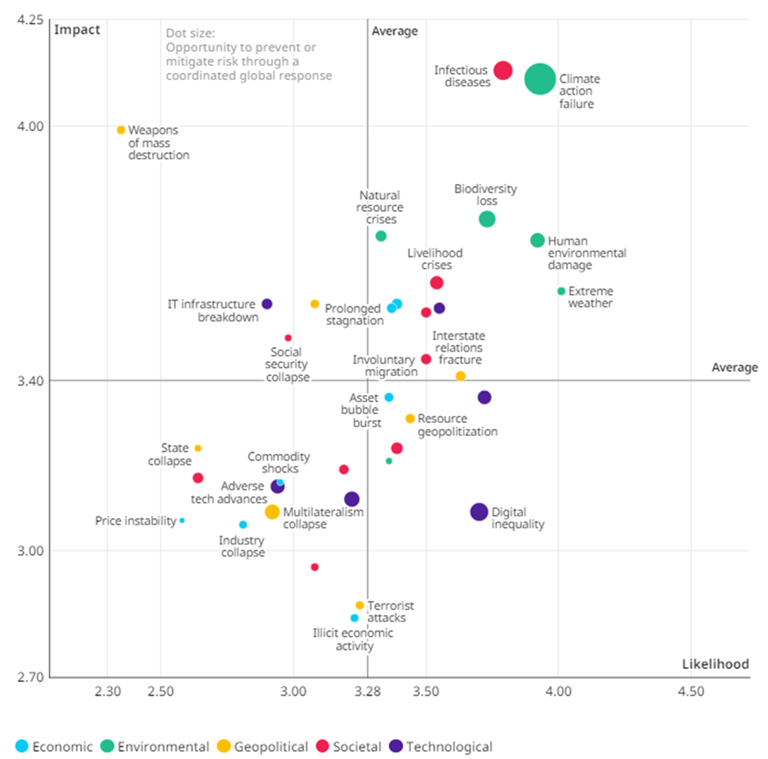

In mid-January the 16th edition of the Global Risks Report was released by the WEF[4]. This report is based on the inputs to surveys of nearly 700 risk experts and decision makers globally. The report is typically published in the lead up to the annual meeting of the WEF in Davos which will be held from 26 to 29 January this year.

The report’s findings highlight how COVID-19 and the variability of responses has increased ongoing geopolitical and societal challenges, noting that the existential threat posed to economies and societies is a great concern globally. It concludes with the statement that “innovative and collaborative approaches to resilience are needed more than ever”. To illustrate the significance of the threat posed by climate change and the current challenges that fragmentation poses, the figure below is included[5] which indicates that there is a higher likelihood for global action on climate to fail than for there to be a threat from infectious diseases; further that the impact of these two risks is extreme. However, there is greater potential to mitigate climate change through a coordinated global response.

Figure 1: The global risk landscape 2021 [6]

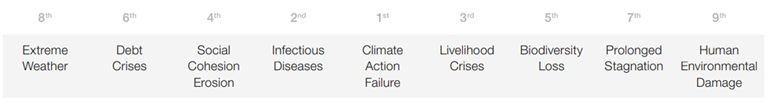

When participants were asked to rank the eight most significant risks, global inaction on climate change was seen as the most significant risk.

Figure 2: Most significant risks in 2021 [7]

Australia, where the bloody hell are you?

With these three major signposts showing how 2021 will unfold for collaboration and cooperation on climate change, the question can be asked, what is Australia doing? With respect to the Federal government’s response the answer would be “very little”. Under the Paris Agreement, countries need to submit their revised NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) every five years. 2020 was the first time that for these five yearly submissions to be made. We saw a flurry of increased ambition through the year with net zero commitments from China, Japan, the UK, Europe and Korea leading the pack. The Australian government submitted an unaltered, low ambition NDC in late December 2020.

On 19 January 2021 Anthony Albanese raised climate change as one of the two major foreign policy issues facing the current government; the other being the relationship that Scott Morrison had with Donald Trump. With respect to climate change Albanese said that [Morrison’s] “positions on climate change will leave the nation more isolated than ever on the international stage”. Given that we are seeing a clear message that climate change is the most significant risk facing economies globally, and that it will take collaboration and concerted action to address these risks, this is a significant challenge for Australia.

What does this mean for business?

Energetics knows better than anyone just how much effort and time Australian companies are putting into understanding and addressing the risks posed to them by climate change. Companies are conducting risk assessments of what a changed global environment means for their business, building resilience plans, setting net zero targets using the best available science, and mapping progress in delivering these. Australian businesses are leading the pack in many ways, some because they are filling the vacuum left by consistent and coherent policy[8].

Furthermore, all Australian states have net zero policies and plans in place to deliver some, if not all, of the necessary emissions reductions.

So why are we concerned about the state of policy at a Federal level, if companies and states are driving us towards zero? Do we need an overarching policy? I would argue yes, for two clear reasons:

- At the moment many actors are doing a lot of work and making great gains; however, if this work was coordinated the gains would be greater. Further, in the long run, if things get really untidy and global pressure is brought to bear, the potential exists for a step change reduction in emissions to be demanded of Australia which could mean a catastrophic change for our economic system as this would impact significantly both what we can buy and what we can sell on the international market.[9]

- We have already started to see some signs of markets requiring specific carbon performance of the inputs they buy. Companies are being asked to provide Environmental Product Declarations or Carbon Footprints for their products. We are also seeing finance starting to move explicitly to assets and companies who both understand and manage the breadth of their climate risks well[10].

We need a consistent and relatively ambitious federal climate change policy which includes specific and clear commitments to realistic emissions reductions on the pathway to net zero by 2050 in order to avoid catastrophic changes to our economic systems and to enable Australian companies to access capital and to continue to sell goods and services internationally.

References

[1] Biden Harris | Plan for Climate Change and Environmental Justice

[3] GOV.UK | Working together to achieve the clean energy transition

[4] World Economic Forum | The Global Risks Report 2021 (16th edition)

[5] Marsh & McLennan Companies | Global Risks Report 2021

[6] World Economic Forum | The Global Risks Report 2021 (16th edition)

[7] World Economic Forum | The Global Risks Report 2021 (16th edition)

[8] RenewEconomy | Climate policy vacuum boosting investor focus on low-carbon assets

[9] The Financial Security Board established by the G20 recognises that climate change is a systemic risk to the financial sector that requires additional scrutiny and further actions to mitigate these risks by the market regulators. In the global financial system, systemic risks are risks that have the potential to destabilise the normal functioning of the system and lead to serious negative consequences for the real economy.

[10] IGCC | Full disclosure: Improving corporate reporting on climate risk