Whatever happened to the National Energy Productivity Plan? We had a target albeit one lacking any aspiration; we had the skeleton of a plan in desperate need of something on its bones, and we understood that significant economic benefits could be delivered. Yet in the ongoing furore over the state of energy and climate policy in this country, the energy productivity opportunity is being ignored as a solution despite its potential for energy cost reductions (in many cases quickly), reducing national energy demand and lowering greenhouse gas emissions.

The realisation of the NEPP would also see a more managed transition of our energy generation fleet from aging coal fired power to renewables and cost effective storage solutions. How? The higher the energy productivity target, the lower the nation’s demand for electricity, resulting in less pressure being placed on generators. Also, as the National Electricity Market preferences renewable energy sources in the merit order, greater quantities of renewable energy are dispatched over coal-fired power and at times, gas-fired generation. And with the Finkel Review’s suite of recommended reforms to market regulation we can address some of the challenges we’ve seen with managing intermittent supply. Throughout this transition, consumers can improve their energy efficiency and lower costs.

In this article we step through the findings of Energetics’ modelling of the impact of different energy productivity targets, and the economic value that can be delivered. We also revisit our work which demonstrates the abatement that can be delivered. We can only hope that someone in Government will dust off the NEPP and take another look.

Energy productivity measures that can help address three challenges

High energy costs

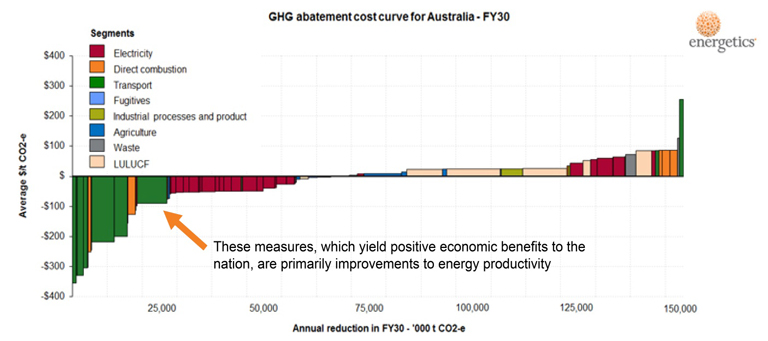

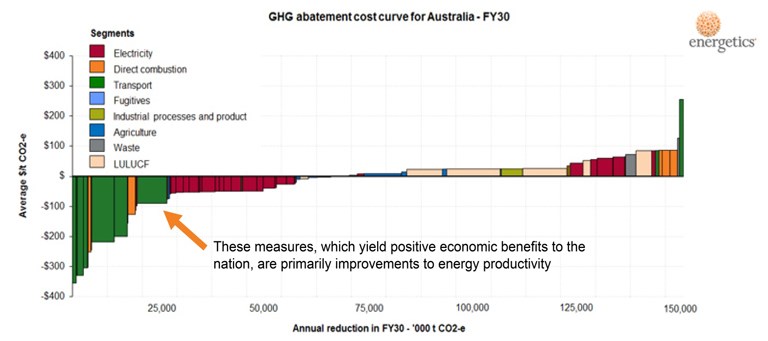

As business and residential consumers struggle with the high cost of energy, the nation has lost sight of the immediate benefits that can be delivered with an energy productivity improvement drive. As Energetics’ demonstrated in our national abatement opportunities modelling there are a raft of measures that yield positive economic benefits to the nation as they reduce energy use. Many of these measures require no capital outlay or minimal capital outlay, and can bring down energy costs immediately. Often these are as simple as changing the way that systems are controlled or scheduled. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Australia's 2030 abatement cost curve (Source: Commonwealth of Australia)

Energy supply security

Energy productivity improvements lower demand for energy. At a time of supply security concerns, driving energy efficiency will in turn reduce the pressure on our energy systems. But as Energetics’ modelling demonstrates, across a number of possible energy productivity scenarios we will have a clear line of sight to the flow on effects on the energy generation mix. Noting, that a well-considered energy productivity improvement plan is only meaningful when supported by a clear and detailed implementation schedule.

Initiatives can be at all scales and all reduce the stress on the energy supply. For instance, many businesses installing solar heaters to pre-heat the feed to industrial boilers will reduce the demand for gas as effectively as a large solar thermal power plant, and at lower cost.

Our modelling of national electricity supply has shown that if don’t improve energy productivity then the nation will struggle to meet its emissions reduction target without a significant uplift in abatement achieved through changes in land use - a near total embargo on further land clearing and tree planning on a vast scale. Even then, we will still see a doubling of the volume of variable renewable generation in the electricity mix.

Alternatively a doubling of energy productivity will see a natural evolution of the generation fleet, with the closure of half of the coal fired power stations, a rise in the fraction of variable renewable generation but importantly a fall in the overall demand for gas fired generation. This means that more gas is available for the firming of the variable renewable generators. AGL has shown that wind firmed with gas generation is the lowest cost option for new generation capacity.

Remember the Paris Climate Agreement?

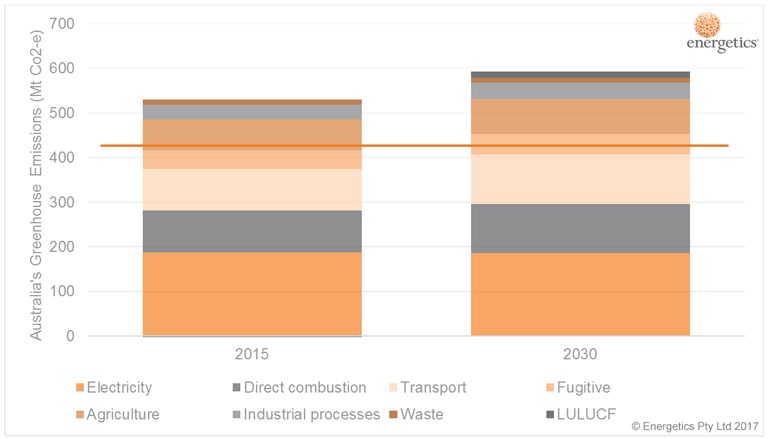

Our commitment to reduce emissions by 28% seems to have been forgotten in the battles over electricity supply. A look at the sources of emissions in Australia and their relationship to the reduction target shows that the energy sector (electricity, fuel combusted for stationary energy and fuel combusted for transport) is responsible two thirds of Australia’s emissions. This sector must deliver the bulk of the abatement needed to meet the 2030 target (see Figure 2 below). The horizontal line shows where emissions must be to achieve the 2030 target. Other parts of the Australian economy will struggle to make a significant contribution. In particular, we have seen the Emissions Reduction Fund soak up the bulk of low cost abatement from the land sector.

Figure 2: Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2015 and 2030

Therefore, meeting our Paris commitment requires either measures to decarbonise energy (policies such as an expanded Renewable Energy Target or Clean Energy Target) or measures that drive down demand for energy (energy productivity). And with the political battlelines being drawn over the proposed Clean Energy Target, once again we see a compelling case for a determined and rapid focus on energy productivity.

Emissions are rising across the economy and this trend needs to be reversed. Energetics’ modelling shows that each tonne of abatement implemented before 2020 displaces over three tonnes of emissions reductions needed over 2020 to 2030. Policy delays create a critical problem not only for our ability to fulfil our international commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement but for the costs that escalate as the abatement task grows and as action is delayed.

It is time that our national leaders find common ground with respect to energy and climate policy. We offer improving Australia’s energy productivity as that common ground.

Note: This thought leadership article was published in RenewEconomy. To view the published article click here.