APRA released a summary of the results of its Climate Vulnerability Assessment (CVA) at the end of last month. The CVA required the four big banks plus Macquarie Bank to assess climate-related risks to credit across their mortgage and business lending portfolios. Two climate scenarios were considered: “Current Policy”, which assumes the Paris Agreement goals will not be met and the world will warm by more than 3oC over this century, and “Delayed Transition”, which assumes that efforts to reach net zero emissions will not begin in earnest until 2030. The first scenario explores risks arising from climate change itself (“physical risk”); the second explores risks resulting from decarbonisation efforts (“transition risk”).

This is not a theoretical exercise. Banks are just starting to integrate climate risk into their credit models, and will take further steps to manage their exposure to high-risk counterparties.

-

Banks will tighten lending terms to manage climate-related credit risks. Some banks will actively reduce lending to regions or sectors vulnerable to physical or transition risk. This creates another vector of climate risk for companies operating in those areas, and these companies will need to be able to show banks they’re managing their climate risk to maintain their access to credit.

-

Banks do not yet have good insight of the physical risks to their customers. Only one bank tried to model the impacts of extreme events. Banks did not model physical risks to non-ag businesses and assumed that business customers could mitigate their risk with insurance.

-

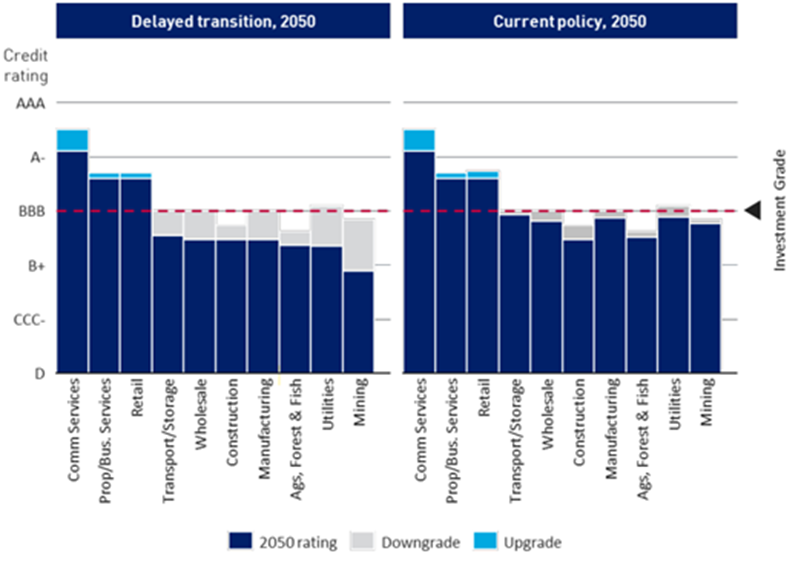

This probably explains why the chart below show such significantly worse impacts to credit ratings under Delayed Transition – most of the impacts of physical risk are not accounted for.

-

Delayed transition results in lending loss rates increasing six-fold in high-risk areas, primarily in the early 2030s. Some banks modelled a gradual recovery thereafter, some estimated a sustained period of high losses. The worst delayed transition losses are in mining, manufacturing and transport but most sectors are impacted.

Why is delayed transition so bad? It reflects the inadequacy of pre-2030 decarbonisation efforts – if we try to achieve the Paris Agreement goals but we wait for another seven years to do so, we’ve got less time to reduce emissions and we need to reduce them more quickly to make up for the emissions that have occurred in the previous decade. This is also harder to do because we have less time to develop and scale new technologies.

It’s important to note that this is the first exercise of its kind for APRA and the Australian banks, although the CVA follows similar exercises by the Banks of England and France and the European Central Bank. The next iterations will probably dive deeper and go broader – and almost certainly reveal more risk is embedded in the loan books. APRA noted that while some differences between banks’ assessed impacts reflected their different portfolios, most of it was probably due to the different levels of skill they brought to their analysis. The banks have all recognised they need to uplift capacity in this area and will get more skilled at assessing their climate-related credit risk and pricing their credit accordingly.

This means that APRA’s headline conclusion – that lending losses “are unlikely to rise to a level that would result in severe stress for the banks” – is at best provisional. As banks improve their ability to consider more climate risks more thoroughly, they will mitigate these risks by redirecting their lending, and high-risk businesses will pay the price.

There is some positive news for companies who need to invest to mitigate their transition risk. The rapid evolution of sustainable finance taxonomies (evidenced by ASFI’s recent consultation paper and Westpac’s discussion paper), their initial focus on climate mitigation, and the inclusion of transition finance (i.e. finance that supports transition to a low-carbon economy) alongside green finance will play a critical role in ensuring capital continues to flow to companies that demonstrate a commitment and a credible plan. It will be up to borrowers to ensure their plans meet these thresholds.

Energetics works with companies facing high transition risk – because they are in emissions-intensive sectors; and high physical risk – those whose operations and supply chains are particularly exposed to climate change. Understanding your climate risk profile is the first step to managing it and developing a credible mitigation strategy – and convincing your financiers that you’re a reliable counterparty.

Figure 1: Counterparty internal credit rating impact (by sector)[1]